Agro-food exports stumble on compliance, certification, and cold chain gaps

November 22, 2025

Bangladesh’s export engine mostly runs on a single fuel: garments. For four decades, the country has stitched its global identity, foreign reserves, and millions of livelihoods into shirts, jeans, and jackets destined for Western markets.

Yet this success comes with a risky paradox. When a single product accounts for 85 percent of the export basket, prosperity becomes fragile—like balancing the nation’s economy on the edge of a sewing needle.

If the country suddenly faces any domestic or global crisis, such as a pandemic, a canceled order, a tariff shift, or a buyer’s change of heart abroad, it could unravel not just factories but the very fabric of Bangladesh’s growth story.

It is valid to ask why Bangladesh has failed to achieve export diversification even after five decades. The country has many untapped options, and among them, agro-food stands out as one of the most viable.

Despite being an agriculture-rich country, Bangladesh struggles to make its mark in the global agro-food export market. The country’s agro-food sector has long lived in the shadow of RMG. While garments stitched the story of export transformation, agriculture still waits for its turn on the global stage.

But the potential is undeniable. With the right strategy, agro-foods can emerge not only as a complementary sector to RMG but also as a cornerstone of inclusive, sustainable growth.

The time to act is now. As Bangladesh moves toward LDC graduation and seeks to diversify its export basket, agro-food is not just an opportunity; it is a necessity.

Agriculture is the heart of Bangladesh’s economy, with the country ranking among the top global producers of freshwater fish, rice, and vegetables, and supporting a growing agro-processing industry.

Despite abundant production of fruits, vegetables, spices, and fish, agro-food exports remain low compared to regional peers, mainly due to weak infrastructure, especially in cold chain management.

For instance, in the last fiscal year (2024-25), Bangladesh earned $988.62 million in the entire year, just up from $964.34 million a year before, according to data from the Export Promotion Bureau (EPB).

Due to insufficient refrigerated transport, limited cold storage, and poor post-harvest handling, a significant portion of perishable goods suffer quality degradation, often making them unfit for export, according to experts and industry insiders.

Another major obstacle is the country’s inability to meet international food safety and quality standards consistently. Global buyers, particularly in the EU, USA, and Japan, demand strict compliance with certifications like Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Point system (HACCP), International Organization for Standardization (ISO), and Global Good Agricultural Practices (GAP).

The post-harvest loss is a major issue. Without reliable cold logistics, Bangladesh cannot maintain the freshness required by high-value export markets, they added.

But most Bangladeshi exporters either lack access to certified labs or face bureaucratic delays in obtaining these approvals. The domestic standards agency BSTI is not fully equipped to issue internationally recognized certifications, and only a small fraction of producers are trained in GAP or food safety protocols.

As a result, many shipments face rejection or are restricted to low-end markets where quality requirements are more relaxed.

“Until recently, we did not have permission to export rice, specifically aromatic rice. Buyers mainly demanded aromatic rice along with other products, but since we couldn’t supply it, we lost many customers. They shifted to other markets because we could not fulfill their requirement,” said Md Shahidul Islam, a senior vice president of Bangladesh Agro-processors Association (BAPA).

“Compliance has become another big barrier. Take halal certification, for example. For years, the Islamic Foundation issued certificates, but now BSTI does it,” he added.

The problem is that in some countries, certificates from the Islamic Foundation are not accepted because it is not listed there. We provided halal certificates, but buyers rejected them, saying they would only accept certification from JAKIM in Malaysia, he added.

Islam, also the managing director of Banoful & Co Limited, said, “We even explained that JAKIM recognizes the Islamic Foundation, but buyers insisted they needed the certificate directly from JAKIM. Without that, they said they could not clear the shipment. This type of issue creates major difficulties for us in different countries.”

“In the case of agribusiness products like spices, many countries demand test reports that cannot be done inside Bangladesh. We have to get these tests done abroad and then provide the certificates. But the process is time-consuming and expensive, which makes us less competitive.”

“Overall, our main problem lies at the policy level, especially certification.”

He said that it’s not that we lack products. The real challenge is that we cannot access certain markets because we cannot meet the specific compliance and certification requirements.”

On top of that, export incentives have gone down. Earlier, we used to receive a 20 percent cash incentive, but now it has been reduced to 10 percent.

“This is a big blow, because that incentive helped us adjust prices and remain competitive in the international market against countries like India, Vietnam, or Malaysia.”

“When we exported goods worth Tk 100, we used to receive Tk 20 as an incentive. That gave us breathing space.”

Islam added that now, with only 10 percent, we can’t match international prices anymore.

For example, if we make biscuits in Bangladesh and export them, the cost is much higher than in India, simply because raw material prices like sugar and flour are much cheaper there.

“Without proper support, it is tough to compete.”

In the agro-export sector, one of the pioneers is the PRAN-RFL group. Talking to the Industry Insider, PRAN-RFL’s Marketing Director Kamruzzaman Kamal said, “Bangladesh has many types of products, but you cannot just export them directly; it has to be done scientifically. There are many certification requirements, and in that area, our country has not developed enough.”

“However, individual manufacturers have developed quality control systems and adopted international standards like us.”

Some facilities we still need to take from the government, and that’s where work is required. For instance, we receive radiation support from the Atomic Energy Commission for exports, but there is actually a bottleneck there, said Kamal.

“We could export a lot more spices, but sufficient radiation support is not available. Expansion in that area is really needed.”

S M Abu Sayed, deputy director (Halal Certification), CM Wing at Bangladesh Standard and Testing Institute (BSTI), however, said there is no complexity in getting certification.

“For medium and large companies, a license is valid for three years, after which it must be renewed.”

Renewal applications have to be submitted three months before expiry. If applied for with urgent fees, the license is usually renewed within 11 working days, he said.

“Currently, around 26 companies hold around 184 licenses from the BSTI, and with our license, companies export to 100-150 countries across the world.”

“We follow the OIC/SMIIC standards (Standards and Metrology Institute for Islamic Countries), which include international halal standards for food, cosmetics, and pharmaceuticals. We have 20-30 expert auditors trained to these standards, each required to score at least 70 out of 100,” he added.

In contrast, the Islamic Foundation does not appear to follow such rigorous standards. BSTI has chemists, pharmacists, BUET chemical engineers, and other qualified professionals ensuring compliance.

When asked about challenges as an exporter, Mr. Kamruzzaman Kamal said, “As an exporter, the main challenges are competitiveness, high prices of raw materials, particularly due to the Russia-Ukraine war, and rising freight costs. Freight is actually a major issue. On top of that, bilateral trade issues, like transport problems with India, also create barriers.”

Currently, we export to 148 countries with all kinds of products. Last fiscal year, our exports closed at around 530 to 540 million dollars, he added.

He suggested for a fresher exporter that for newcomers who want to enter the export market, my advice is obvious: ensure quality compliance.

“At every stage of food production, there are compliance requirements. Food safety can be compromised at any step, so maintaining international standards is essential.”

Professor Mohammad Jahangir Alam, a professor of agrobusiness and marketing at Bangladesh Agricultural University (BAU), said, “Apart from RMG, no other export commodity has grown significantly in Bangladesh. This is what economists often call the Dutch Disease, when an economy depends too heavily on a single sector, and any vulnerability in that sector impacts the whole economy.

Agriculture had the potential to be the ‘second best’ sector because production has increased. But agricultural output is partly seasonal. Fruits, for example, flood the market during harvest, prices collapse, and the same is true for vegetables, he said.

“If we could add value through processing and export, the outcome would be very different.”

Unfortunately, sending just two cartons of mangoes abroad often makes headlines, but that is negligible compared to what countries like Japan and South Korea are doing. They are exporting processed agro-commodities in bulk and earning significant foreign currency. Bangladesh, too, has this potential.

“The first barrier is safety and certification. International markets require strict compliance with GAP (Good Agricultural Practices) and GMP (Good Manufacturing Practices). Without GAP and GMP certification, buyers in the Middle East or the US will never accept our products. This remains a major challenge.”

“Although there has been some progress under the World Bank-funded PARTNER project, certification is still a bottleneck. What we need is a one-stop certification authority to issue internationally acceptable GAP and GMP certificates.”

Transportation and cold chain management are other big problems. Perishable products need proper cold storage and fast shipment. But since these are not prioritized, freight costs are very high, and that makes our products uncompetitive abroad.

According to Prof Alam, “Our embassies also need to play a stronger role. Too often, they remain busy with consular work, while their commercial sections should promote our products and build trade relationships. Mango promotion events in Dubai are good examples, but such efforts must be continuous.”

“Packaging is another area where we struggle. Most packaging materials are imported, making it expensive. If agro-food packaging industries were developed locally, it would help exporters greatly.”

“If Bangladesh is serious about diversifying exports beyond RMG, then four to five key areas must be addressed: GAP/GMP certification, cold chain and freight facilities, active promotion through embassies, and affordable packaging. Only then can agro-food emerge as the second major export sector.”

Arif Hossain Khan, spokesperson of the Bangladesh Bank, acknowledged the lag in the agro-export situation.

“Although Bangladesh lags in the agro export, we have enough support for the exporters with a refinance facility,” he said.

“We have an annual agricultural credit policy and a special agricultural fund. Each bank is assigned a lending target for agricultural credit,” he said.

If a bank cannot meet its target due to network limitations, the shortfall is deposited into a compulsory fund managed by Bangladesh Bank, which then channels loans through institutions capable of disbursing them.

Additionally, there are incentives for cultivating crops like ginger and turmeric in the hill tracts, as well as cash incentives for export-oriented agricultural products. We treat agriculture as a priority sector,” he added.

“For projects related to agro-processing and storage—not raw production—we have an Enterprise Equity Fund. It provides very low-interest loans and financial support for eligible projects.”

“Exporters have access to LC facilities to bring raw materials and other institutional support.”

We definitely patronize agricultural exports and provide various types of incentives, including cash support.

Earlier, exporters could get a 20% cash incentive, which has now been reduced. Some exporters have suggested increasing it to 30–32% to offset losses from LDC graduation and maintain competitiveness.”

“Graduation brings prestige as a middle-income country, but we lose advantages such as GSP benefits. Many sectors face cuts, which creates shocks for businesses. Some have proposed deferring graduation slightly, citing political turbulence and the need to achieve stability before meeting targets. If such a deferral can be negotiated, it could benefit the country.”

Khan, however, said considering our population of 180 million across 56,000 square miles, the country actually imports more agro products, around Tk 25,000 crore, than we export.

For instance, we import soybeans because we cannot produce enough domestically. If we can create import-substitute products, that can help our trade balance, he said.

According to the Bangladesh Investment Development Authority (BIDA), recognized as a priority sector for export diversification, agriculture and food processing have demonstrated strong momentum.

The industry has recorded a 13 percent compound annual growth rate, with processed food exports growing at 16.6 percent per annum. Bangladesh currently exports over 700 products to 140+ countries, supported by duty-free or preferential access to 52 markets, including the EU, GCC, and ASEAN regions, it said.

Backed by policy incentives and private sector growth, the sector has evolved into a vibrant agribusiness ecosystem, with 1,000-plus food processors and 250 exporters.

“However, with over 75 percent of agricultural produce still unprocessed, the potential for value addition remains significantly underutilized.”

Priority investment areas include agro-processing and food manufacturing; sustainable cold chain and storage infrastructure; seed technology; climate-smart agriculture and climate-resilient crops; modern packaging, logistics, and contract farming; as well as digital agri-tech platforms, IoT-led precision farming, and traceability technologies.

An expansive and growing domestic market, valued at $47.54 billion as of 2022. With a population exceeding 170 million and an emerging MAC of 34 million, demand for high-quality, processed, and branded food products is on the rise.

The halal food segment, in particular, is growing at 8-10% annually, aligning Bangladesh with the rapidly expanding $2.4 trillion global halal market. Yet, Bangladesh is nowhere near leveraging its potential.

Asked why Bangladesh lags in exports, Mr. Abu Sayed said, “Frankly, I see no reason why Bangladesh should lag in agro-exports.”

“For example, in Bangladesh, puffed rice (muri) costs Tk 80–90 per kg, but when I was performing Hajj, I bought the same product for Tk 250–300 per kg in Saudi Arabia.”

“Now imagine exporting that Tk 100 worth of muri to Makkah or Madinah. On top of that, the government provides Tk 25 in incentives. With proper LC documentation, exporters receive this incentive from the Bangladesh Bank every two months,” explained Mr. Abu Sayed.

So, where is the loss? Why should a producer blame the system? From my perspective, there is no major challenge from the regulatory bodies, no significant harassment, and no insurmountable barriers. I openly challenge anyone to point out where exactly the problem lies.

We should not underestimate ourselves. If the products are good, the standards are met, and the incentives are available, there is no reason Bangladesh cannot succeed in agro-exports.

Md Asaduz Zaman is a Bangladeshi journalist who covers Bangladesh’s economy, environment, and agriculture sectors.

Most Read

Starlink, satellites, and the internet

BY Sudipto Roy

August 08, 2025

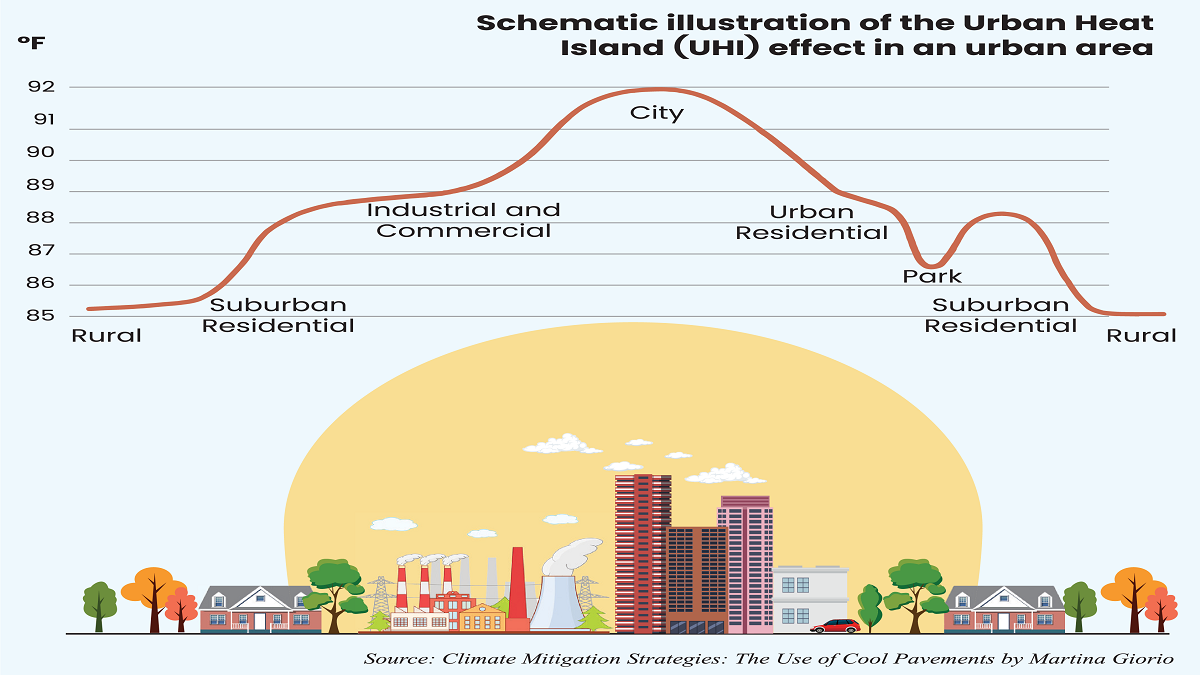

What lack of vision and sustainable planning can do to a city

From deadly black smog to clear blue sky

A nation in decline

Understanding the model for success for economic zones

How AI is fast-tracking biotech breakthroughs

Environmental disclosure reshaping business norms

Case study: The Canadian model of government-funded healthcare

A city of concrete, asphalt and glass

Does a tourism ban work?

You May Also Like